Jacqui Murray and her family were camping Sunday on Australia’s K’Gari (Fraser Island) when their three-year-old daughter Luna went into anaphylactic shock from a jellyfish sting.

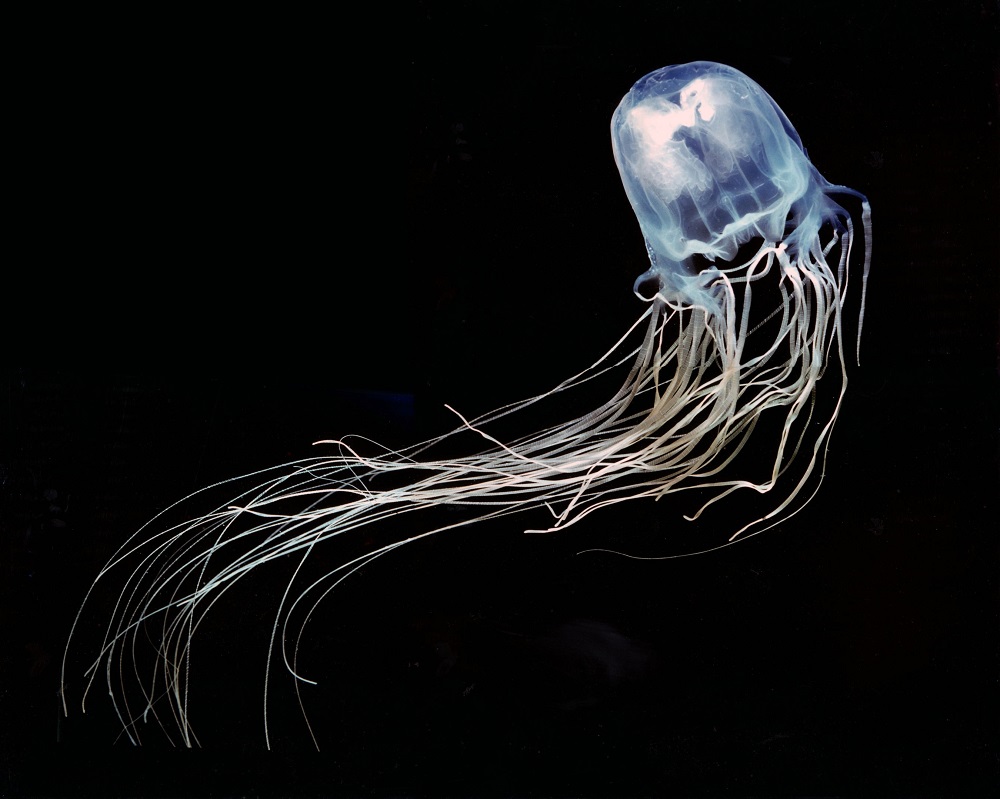

The Irukandji common to the island is a small venomous species of box jellyfish about an inch in diameter, making them hard to spot in the water. Their sting is generally mild but can be life-threatening if anaphylaxis is triggered.

Luna’s was one of four jellyfish stings reported on the island in a two-day span, with a teenage girl needing to be airlifted to a hospital in another case.

Luckily, Ms Murray had the foresight to pack an epinephrine auto-injector as a “just in case, precautionary measure” for their vacation.

She picks up the story:

We were up with the kids early, and I had my baby in my arms.

Two of my biggest kids were in the water, and they were trying to lure Luna into further depths.

As soon as [Luna] came out of the water, she said, ‘the saltwater’s stinging me.’

I immediately ripped off her bathers and I could see the bites on her body were significant, about six by six inches on her tummy, one under her arm and one in her bikini area.

Ms Murray gave Luna antihistamines and acetaminophen as soon as she emerged from the water, but her symptoms worsened. She said Luna was “foaming at the mouth,” vomiting, and “going in and out of consciousness” when she used the SOS function on her iPhone to call for help.

I managed to get through to [emergency services], who then contacted the ambulance at Happy Valley, on the eastern side of the island.

They could not get through due to the high tide, and then unfortunately their call dropped out.

I was standing on a rock with my phone in the air, trying to monitor my three-year-old who was having a severe reaction, mid-crisis, and no contact.

A rescue helicopter landed at the campsite some time later, but by that time, the mom had already administered the epinephrine.

It’s not something you want to do.

That needle is quite significant for a little three-year-old … but it’s something that has saved her life in this situation.

The EpiPen adrenaline lasted for about 15 minutes, she came good, and then she started declining again, so I had to make another [call to emergency services].

By that time, they said that the helicopter was on their way.

Luna was admitted to Hervey Bay Hospital, where she spent the next three days, during which Ms Murray was unable to contact Luna’s father and five siblings who remained on the island.

She was going high heart rate to low heart rate with high blood pressure and low blood pressure drops with continuous vomiting and not being able to keep any fluids down, so it hasn’t been a fun time.

And not being able to communicate the situation back to my husband and the other children has been also very challenging.

Ms Murray and Luna returned to the family on K’Gari for the last week of their camping vacation.

She has since urged authorities to install emergency phones, wash stations and warning signs to prevent future stinging incidents.

Although it’s not clear how Ms Murray obtained her epinephrine auto-injector, we are grateful she brought it along and administered it, and by doing so likely saved Luna’s life.

In some cases, venomous stings can cause severe, life-threatening reactions in individuals with no history of allergy. For that reason, it is essential that as many people are trained to carry and administer epinephrine as possible.

We support Dillon’s Law, recently introduced to Congress, which would give states incentives to adopt programs that would train, certify, and indemnify citizens to carry stock epinephrine and administer it in an emergency.

Dillon’s Law Promoting The Carrying and Administration of Epinephrine Introduced to Congress