Researchers from the Technical University of Munich (TUM) presenting their findings at the annual convention of the European Society for Dermatological Research (ESDR), demonstrated that intestinal bacteria play a role in determining the severity of anaphylactic reactions in food allergy.

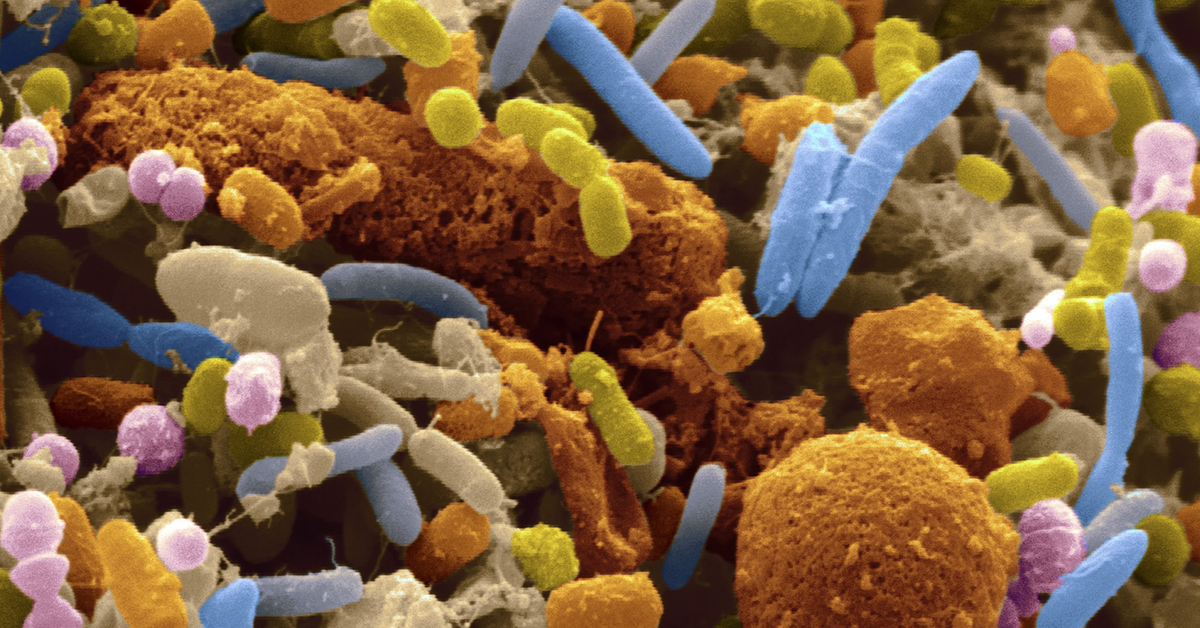

The human gut, populated by billions of bacteria, is known to play a critical role in the health of its host. Dr Tilo Biedermann and his colleagues focused their study on a protein called NOD2, a receptor of the immune system known to “recognize” intestinal bacteria and trigger numerous complex processes.

The team showed that when NOD2 was absent, the body’s immune reaction was fundamentally changed, producing fewer regulatory T cells – which suppress immune reactions – and more Th2 helper cells.

Th2 in turn cause more antibody immunoglobulin E (IgE) cells to be produced. In people with food allergies, IgE cells are “trained” to recognize specific allergens and trigger reactions. The more IgE present, the stronger the reaction.

When the researchers observed the absence of NOD2 in mouse models, they noticed the composition of their intestinal microbiota also changed. When the composition of the microbiota was re-normalized, they observed that serious reactions could be prevented even in the absence of NOD2.

“This relationship between intestinal flora and the production of antibodies opens up new therapeutic approaches for patients whose microbiota is altered”, said Biedermann. “For example, if it is possible to encourage harmless bacteria to colonize the intestines, this would also reduce the body’s reaction to allergens.”

The study has yet to be published.