Our food supply is becoming increasingly fragile as the world deals with global climate change. As a result, food manufacturers are constantly searching for new sources of protein, such as vegan meat substitutes and meat grown entirely from plants.

One such alternative is insects. Insects have been consumed for millenia by many cultures indigenous to Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Oceania and offer a rich source of protein that is easily farmed and consumes far fewer resources to raise.

Manufacturers are experimenting with ways to make insect-based products more palatable to western culture, such as by grinding crickets into flour and incorporating them into traditional foods. But the practice comes with dangers for the food allergy community.

Here follows research from James Cook University warning that food containing insect-based ingredients may pose a hazard to people with crustacean shellfish allergy.

James Cook University researchers say food derived from crickets and flies can cause allergic reactions in people with existing shellfish allergy – and this is not consistently picked up by currently available testing methods.

Professor Andreas Lopata and Dr Shay Karnaneedi from JCU’s Australian Institute of Tropical Health and Medicine said edible insect proteins are increasingly manufactured for consumption by people and pets as a sustainable way to feed the world’s growing population.

Professor Lopata, team leader and head of the Molecular Allergy Research Laboratory, said insects are highly nutritious due to their high protein content and eating them is also good for the planet, supporting Australia’s circular economy and decarbonisation approaches.

“The trouble is that insects are closely related to crustaceans such as prawns, crabs, and lobsters. Crustacean food allergy affects up to 4% of the population, with those people at significant risk of suffering from an allergic reaction after eating insect protein-based foods,” said Professor Lopata.

The team studied seven cricket and two black soldier fly-based food products for their protein content and potential to trigger allergic reactions. Two commercial food allergen test kits were analysed for their ability to safeguard consumers.

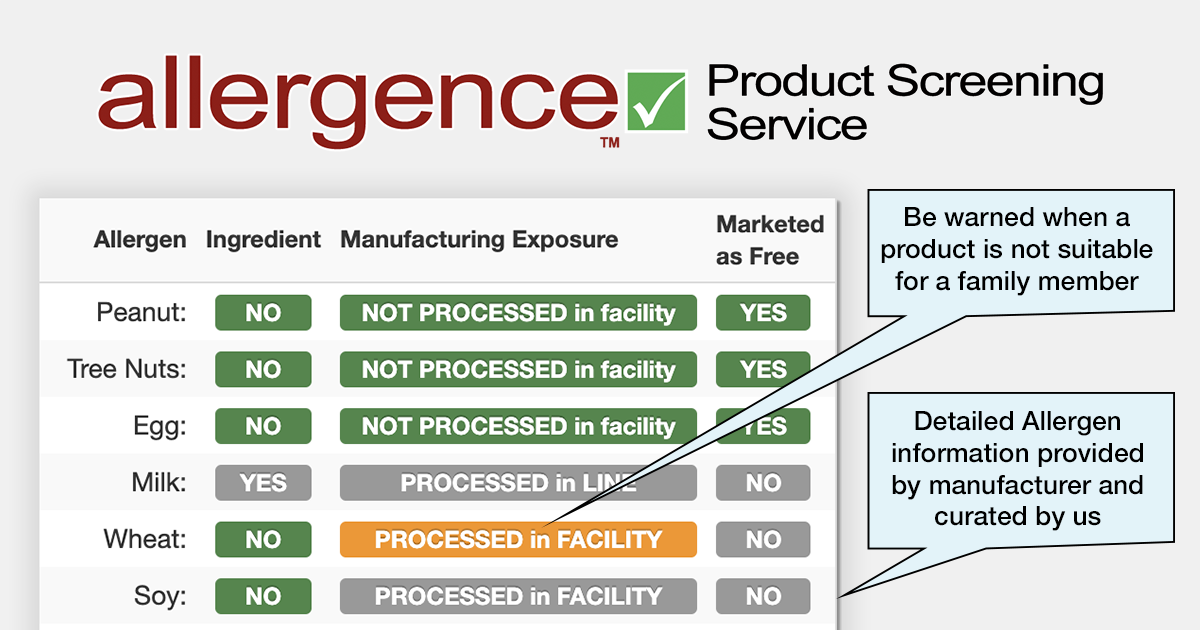

“We identified proteins (allergens) in insect-based food that can cause allergic reactions in people with shellfish allergy. But we found commercial crustacean allergen test kits did not reliably indicate this,” said Dr Karnaneedi.

“It means food allergen test kits and food allergen labelling must take into account these unique allergens in edible insects, especially as this will likely be a primary source of food protein for the growing human population,” said Dr Karnaneedi.

“And shellfish allergy sufferers must be aware of potential risks posed by insect-based foods.”

The team also used advanced mass spectrometry methods to characterise the proteins, and even that raised challenges.

“Our study demonstrated that how you chose to extract the insect proteins impacted the identification of allergens within different insect species,” said Professor Michelle Colgrave of CSIRO and Edith Cowan University.

“More research to standardise detection is needed,” she said.

The JCU team published its study together with collaborators at the Australian National Measurement Institute (NMI), Australia’s national science agency (CSIRO), Edith Cowan University (ECU), Singapore’s Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR), and Dr Thimo Ruethers from JCU’s Tropical Futures Institute (TFI) in Singapore, where 16 different insect species were recently approved for human consumption:

S. Karnaneedi, E. B. Johnston, U. Bose, A. Juhász, J. A. Broadbent, T. Ruethers, E. M. Jerry, S. D. Kamath, V. Limviphuvadh, S. Stockwell, K. Byrne, D. Clarke, M. L. Colgrave, S. Maurer-Stroh, A. L. Lopata, The Allergen Profile of Two Edible Insect Species—Acheta domesticus and Hermetia illucens. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 2024, 2300811. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.202300811

Learn more about insect food allergies and shellfish allergy diagnosis.