Northwell and Stacker analyze theories like underexposure to allergens and an increase in processed foods

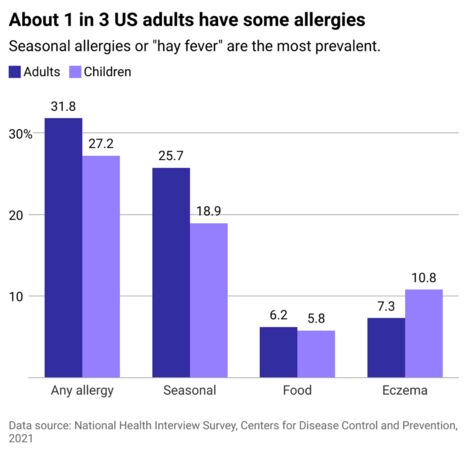

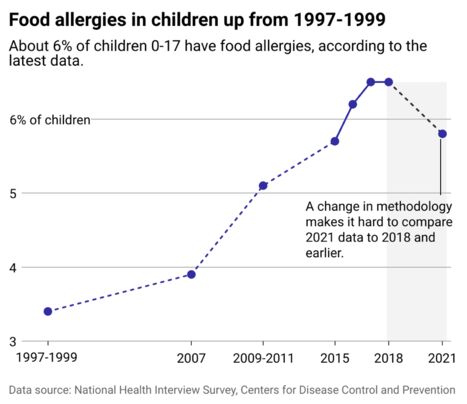

About 1 in 3 adults in the U.S. have some type of allergy, according to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, along with more than 1 in 4 children. Those numbers represent dramatic increases in allergy cases among the population: Food allergies among children doubled from 2000 to 2018.

Northwell Health partnered with Stacker to examine the increasing rate of allergies using data from the National Health Interview Survey.

An allergy occurs when the immune system overreacts to a substance or environment by mistaking it for a pathogen, producing an exaggerated immune response that can include fatigue, swelling, rashes, congestion, coughing and wheezing, or anaphylaxis, per the National Institutes of Health.

Ironically, our allergies may have gotten worse because of the eradication of certain pathogens—like parasites, including hookworms and tapeworms—within the United States. According to this theory, the absence of a known threat leads the immune system to attend to less-threatening and often harmless “invaders.” To explore this theory, some researchers have deliberately introduced parasites into their own bodies to assess the impact on allergic responses. The study (though limited in scope) did suggest that the introduction of a parasite led to immunosuppression.

This data, coupled with recent study outcomes, demonstrates the interconnectedness of the body’s immune responses. While just over 7% of the surveyed adult participants reported eczema, an Australian study demonstrated that the severity of eczema in babies may be linked to the eventual development of food allergies.

Another connection to a spike in allergies comes from a lack of exposure. To quell a rise in allergy cases, the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2000 recommended that children younger than 3 not be exposed to peanuts—thereby actually increasing the likelihood of a child developing an allergy by not interfacing with the legume sooner. Today, it’s widely recommended that infants between 6 and 12 months of age should be introduced to peanuts.

Another theory suggests that the food we eat today is at odds with the microbiota in our bodies that coevolved along with humans—and which are not designed to interact with processed foods.

The difference between an allergy and sensitivity, however, may not always be obvious. A true allergic reaction to a food typically involves difficulty breathing or a drop in blood pressure, per Harvard Health Blog. In contrast, food sensitivities evoke much less severe reactions, such as fatigue and general malaise.

The Food and Drug Administration is keeping pace with such advances by updating its list of major food allergens, which mandates the labeling of any product that has or contains a derivative of any item on the known allergen risk list. As of 2023, the list includes peanuts, tree nuts, milk, egg, wheat, fish, shellfish, soybeans, and sesame.

Seasonal allergies are the most common

More than a quarter of American adults reported experiencing seasonal allergies, which typically comprise environmental substances like ragweed, tree and grass pollen, and mold spores. However, environmental allergies are not always necessarily seasonal; some individuals’ immune systems respond harshly to year-round substances such as dust and dander.

Some researchers posit that seasonal allergies are worsening due to climate change, given that many plants are blooming more often—thus releasing pollen earlier and for a longer period of time, particularly in the case of ragweed.

Battling seasonal allergies long-term can take a toll on the body in unexpected ways. According to the Harvard School of Public Health, the presence of sugar in mucus can attract bacteria, leaving allergy sufferers more susceptible to developing disease over time.

Luckily, advances in immunotherapy options show promise for the treatment and potential cure of allergies. Each treatment type—allergy shots and sublingual immunotherapy—involves gradually exposing the individual to the allergen to increase their tolerance and is generally most effective for environmental allergens.

Food allergies in children have spiked

While food allergies only comprised 6% of all reported allergies, their presence within the population is surging. Consequently, so is research into their prevention. The aforementioned practice of gradually exposing an individual to their allergen is a far cry from previously issued advice.

When the AAP’s 2000 recommendation to delay children’s exposure to peanuts failed to reduce peanut allergies within the population, the academy retracted its advice. New guidelines issued by the Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology in 2017 instruct parents to expose their children to peanuts when they are infants to reduce the chance of developing a major intolerance or allergy.

Not only does the avoidance of developing allergies reduce health risks related to overactive immune responses, but it also allows children to consume more nutrient-dense foods. In fact, recent research into the impact of allergies suggests that long-term avoidance of food allergies may significantly impact children’s nutrition and development, per the NIH. Ultimately, amid steadily increasing rates of pediatric hospitalization due to anaphylaxis, prevention remains the best defense.